Reclaiming the Web with a Personal Reader

Background

Last year I experienced the all-too-common career burnout. I had a couple of bad projects in a row, yes, but more generally I was disillusioned with the software industry. There seemed to be a disconnection between what I used to like about the job, what I was good at, and what the market wanted to buy from me.

I did the usual thing: I slowed down, quit my job, started therapy. I revised my habits: eat better, exercise, meditate. I tried to stay away from programming and software-related reading for a while. Because I didn’t like the effect it had on me, but also encouraged by its apparent enshittification, I quit Twitter, the last social media outlet I was still plugged into.

Not working was one thing, but overcoming the productivity mandate —the feeling that I had to make the best of my time off, that I was “recharging” to make a comeback— was another. As part of this detox period, I read How to Do Nothing, a sort of artistic manifesto disguised as a self-help book that deals with some of these issues. The author Jenny Odell mentions Mastodon when discussing alternative online communities. I had heard about Mastodon, I had seen some colleagues move over there, but never really looked at it. I thought I should give it a try.

∗ ∗ ∗

I noticed a few things after a while on Mastodon.

First, it felt refreshing to be back in control of my feed, to receive strictly chronological updates instead of having an algorithmic middleman trying to sell me stuff.

Second, many people were going through a similar process as mine, one of discomfort with the software industry and the Web. Some of them were looking back at the old times for inspiration: playing with RSS, Bulletin Board Systems, digital gardens, and webrings; some imagined a more open and independent Web for the future.

Third, not only wasn’t I interested in micro-blogging myself, but I didn’t care for most of the updates from the people I was following. I realized that I had been using Twitter, and now Mastodon, as an information hub rather than a social network. I was following people just to get notified when they blogged on their websites; I was following bots to get content from link aggregators. Mastodon wasn’t the right tool for that job.

Things clicked for me when I learned about the IndieWeb movement, particularly their notion of social readers. Trying Mastodon had been nice, but what I needed to reconnect with the good side of the Web was a feed reader, one I could adjust arbitrarily to my preferences. There are plenty of great RSS readers out there, and I did briefly try a few, but I knew this was the perfect excuse for me to get back in touch with software development: I was going to build my own personal reader.

Goals

As a user, I had some ideas of what I wanted from this project.

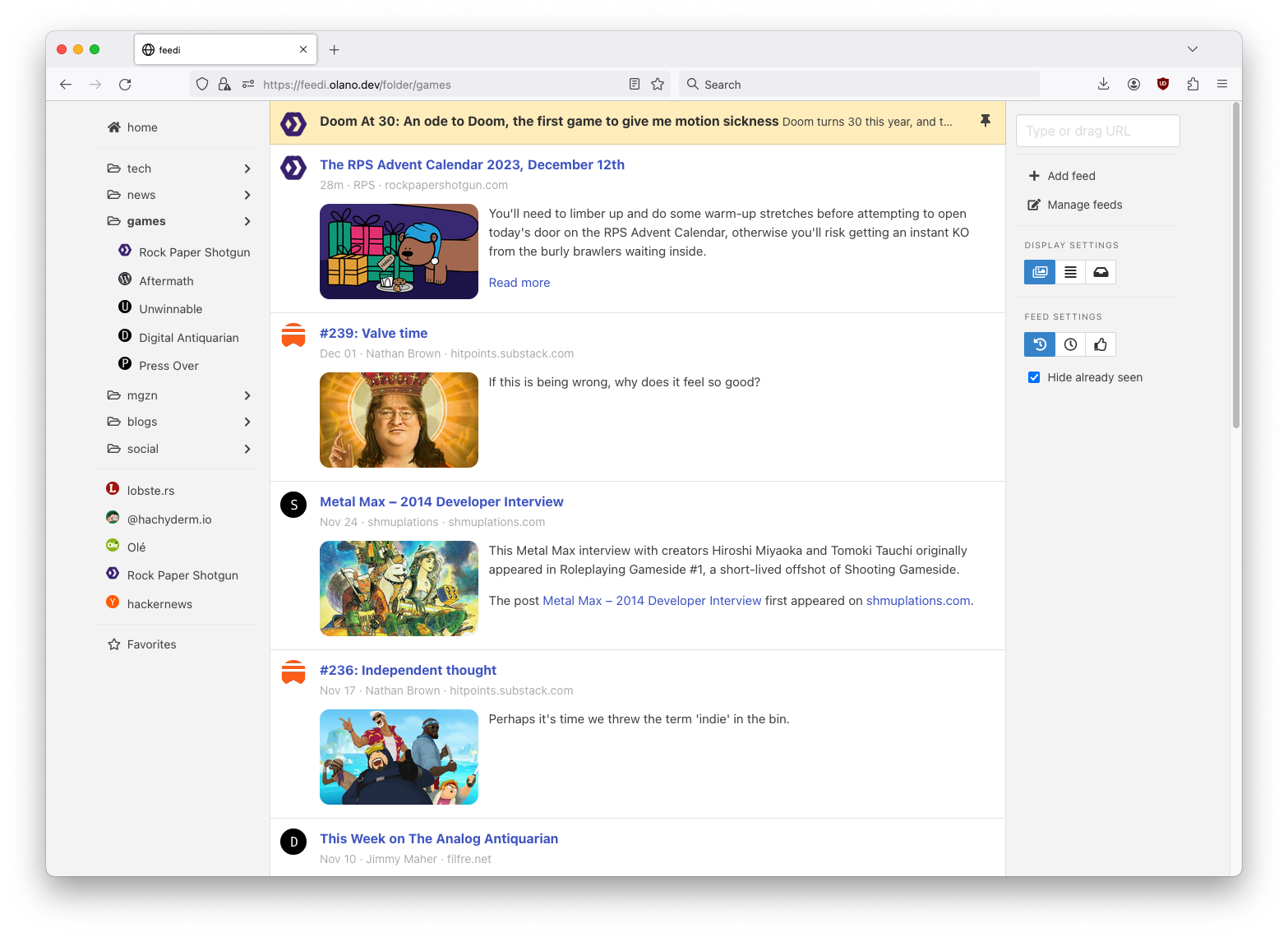

Rather than the email inbox metaphor I’ve most commonly seen in RSS readers, I wanted something resembling the Twitter and Mastodon home feed. That is: instead of a backlog to clear every day, a stream of interesting content whenever I opened the app. The feed would include articles from blogs, magazines, news sites, and link aggregators, mixed with notifications from personal accounts (Mastodon, Goodreads, GitHub). The parsing should be customizable to ensure a consistent look and feel, independent of the shape of the data each source published.

I wasn’t interested in implementing the “social” features of a fully-fledged indie reader. I didn’t mind opening another tab to comment, nor having my “content” scattered across third-party sites.

That’s what I started with but, once I had the basic functionality in place, I planned to drive development by what felt right and what felt missing as a user. My short-term goal was to answer, as soon as possible, this question: could this eventually become my primary —even my sole— source of information on the Web? If not, I’d drop the project right away. Otherwise, I could move on to whatever was missing to realize that vision.

∗ ∗ ∗

As a developer, I wanted to test some of the ideas I’d been ruminating on for over a year. Although I hadn’t yet formulated it in those terms, I wanted to apply what I expressed in another post as: user > ops > dev. This meant that, when prioritizing tasks or making design trade-offs, I would choose ease of operation over development convenience, and I would put user experience above everything else.

Since this was going to be an app for personal use, and I had no intention of turning it into anything else, putting the user first just meant dogfooding: putting my “user self” —my needs— first. Even if I eventually wanted other people to try the app, I presumed that I had a better chance of making something useful by designing it ergonomically for me, than by trying to satisfy some ideal user. It was very important to me that this didn’t turn into a learning project or, worse, a portfolio project. This wasn’t about productivity: it was about reconnecting with the joy of software development; the pleasure wouldn’t come from building something but from using something I had built.

Assuming myself as the single target audience meant that I could postpone whatever I didn’t need right away (e.g. user authentication), that I could tackle overly-specific features early on (e.g. send to Kindle), that I could assume programming knowledge for some scenarios (e.g. feed parser customization, Mastodon login), etc.

Design

Given that mental framework, I needed to make some initial technical decisions.

User Interface

Although this was going to be a personal tool, and I wanted it to work on a local-first setup, I knew that if it worked well I’d want to access it from my phone, in addition to my laptop. This meant that it needed to be a Web application:

- it was the cost-effective way to have a single interface work for both devices,

- it allowed me to use HTML and CSS (the UI technology I’m most familiar with),

- it solved device syncing by having the state stored on the server.

I wanted the Web UI to be somewhat dynamic, but I didn’t intend to build a separate front-end application, learn a new front-end framework, or re-invent what the browser already provided. Following the boring tech and radical simplicity advice, I looked for server-side rendering libraries. I ended up using a mix of htmx and its companion hyperscript, which felt like picking Web development up where I’d left off over a decade ago.

Architecture

Making the app ops-friendly meant not only that I wanted it to be easy to deploy, but easy to set up locally, with minimal infrastructure —not assuming Docker, Nix, etc.

A “proper” IndieWeb reader, at least as described by Aaron Parecki, needs to be separated into components, each implementing a different protocol (Micropub, Microsub, Webmentions, etc.). This setup enforces a separation of concerns between content fetching, parsing, displaying, and publishing. I felt that, in my case, such architecture would complicate development and operations without buying me much as a user. Since I was doing all the development myself, I preferred to build a monolithic Web application. I chose SQLite for the database, which meant one less component to install and configure.

In addition to the Web server, I needed some way to periodically poll the feeds for content. The simplest option would have been a cron job, but that seemed inconvenient, at least for the local setup. I had used task runners like Celery in the past, but that required adding a couple of extra components: a consumer process to run alongside the app and something like Redis to act as a broker. Could I get away with running background tasks in the same process as the application? That largely depended on the runtime of the language.

Programming language

At least from my superficial understanding of it, Go seemed like the best fit for this project: a simple, general-purpose language, garbage-collected but fast enough, with a solid concurrency model and, most importantly for my requirements, one that produced easy-to-deploy binaries. (I later read a similar case for Golang from the Miniflux author). The big problem was that I’d never written a line of Go, and while I understood it’s a fairly accessible language to pick up, I didn’t want to lose focus by turning this into a learning project.

Among the languages I was already fluent in, I needed to choose the one I expected to be most productive with, the one that let me build a prototype to decide whether this project was worth pursuing. So I chose Python.

The bad side of using Python was that I had to deal with its environment and dependency quirks, particularly its reliance on the host OS libraries. Additionally, it meant I’d have to get creative if I wanted to avoid extra components for the periodic tasks. (After some research I ended up choosing gevent and an extension of the Huey library to run them inside the application process).

The good side was that I got to use great Python libraries for HTTP, feed parsing, and scraping.

Testing (or lack thereof)

I decided not to bother writing tests, at least initially. In a sense, this felt “dirty”, but I still think it was the right call given what I was trying to do:

- Since I was going to experiment, adding, removing, and rearranging features, the cost of maintaining unit tests would outweigh their value. I didn’t mind introducing little logic bugs; I was going to use the app myself anyway, so I expected that most significant bugs would just surface over time.

- In my experience, integration tests are the ones that provide the most value in terms of confidence that the application works as expected. More so for this project, where the bulk of the work (and the majority of the bugs) came from interacting with external sources and from the UI. But, while I could have caught some bugs earlier and prevented some regressions if I had integration tests in place, implementing them required an effort that just wasn’t worth it upfront.

Development

There’s a kind of zen flow that programmers unblock when they use their software daily. I don’t mean just testing it but experiencing it as an end user. There’s no better catalyst for ideas and experimentation, no better prioritization driver than having to face the bugs, annoyances, and limitations of an application first-hand.

After some trial and error with different UI layouts and features, a usage pattern emerged: open the app, scroll down the main feed, pin to read later, open to read now, bookmark for future reference.

I decided early on that I wanted the option to read articles without leaving the app (among other things, to avoid paywalls and consent popups). I tried several Python libraries to extract HTML content, but none worked as well as the readability one used by Firefox. Since it’s a JavaScript package, I had to resign myself to introducing an optional dependency on Node.js.

With the basic functionality in place, a problem became apparent. Even after curating the list of feeds and carefully distributing them in folders, it was hard to get interesting content by just scrolling items sorted by publication date: occasional blog posts would get buried behind Mastodon toots, magazine features behind daily news articles. I needed to make the sorting “smarter”.

Considering that I only followed sources I was interested in, it was safe to assume that I’d want to see content from the least frequent ones first. If a monthly newsletter came out in the last couple of days, that should show up at the top, before any micro-blogging or daily news items. So I classified sources into “frequency buckets” and sorted the feed to show the least frequent buckets first. Finally, to avoid this “infrequent content” sticking at the top every time I opened the app, I added a feature that automatically marks entries as “already seen” as I scroll down the feed. This way I always get fresh content and never miss “rare” updates.

∗ ∗ ∗

At first, I left the app running on a terminal tab on my laptop and used it while I worked on it. Once I noticed that I liked what was showing up in the feed, I set up a Raspberry Pi server in my local network to have it available all the time. This, in turn, encouraged me to improve the mobile rendering of the interface, so I could access it from my phone.

I eventually reached a point where I missed using the app when I was out, so I decided to deploy it to a VPS. This forced me to finally add the authentication and multi-user support I’d been postponing and allowed me to give access to a few friends for beta testing. (The VPS setup also encouraged me to buy a domain and set up this website, getting me closer to the IndieWeb ideal that inspired me in the first place).

Conclusion

It took me about three months of (relaxed) work to put together my personal feed reader, which I named feedi. I can say that I succeeded in reengaging with software development, and in building something that I like to use myself, every day. Far from a finished product, the project feels more like my Emacs editor config: a perpetually half-broken tool that can nevertheless become second nature, hard to justify from a productivity standpoint but fulfilling because it was built on my own terms.

I’ve been using feedi as my “front page of the internet” for a few months now. Beyond convenience, by using a personal reader I’m back in control of the information I consume, actively on the lookout for interesting blogs and magazines, better positioned for discovery and even surprise.

2023-12-12